Friday, July 29, 2005

The Southern California Economy's Biggest Export

Saturday, June 25, 2005

Book Review: Mike Davis, City of Quartz

Photo of LA riots: http://www.urbanvoyeur.com/

a couple of months ago i was in downtown los angeles on business. it was probably the first time i had been downtown since i was a kid. i stayed in a beautiful old hotel (thanks, boss!) right on pershing square. a couple of things struck me the very first day. pershing square was filled with insane - and sometimes belligerent - homeless people. the area up the hill was encrusted with high rise bank buildings and a plethora of cultural institutions, including the new geary concert hall. Down the hill, on broadway, the street was lined with boarded-up deco theatres and decrepit Mexican utility and t-shirt shops. And, incredibly to me, right on the square, there was a subway station.

What is los angeles? It seems to defy characterization at times, encompassing every type of person and thing, but not dominated by any one. Spread over a vast basin between the beach and the mountains, its history is short, and bathed in Hollywood imagery. It is criss-crossed with freeways. Nobody walks. Everybody is tan and happy. It's the city everybody loves to hate.

About the same time I took my trip, a good friend gave me a book entitled "City of Quartz." The first of a trilogy of books on los angeles, it addresses some of the many facets that make l.a. what it is. Its author, mike davis, a former trucker, meatcutter, now a professor and an avowed Marxist, brings a lot of his own critical perspective to bear. At certain points he evokes an l.a. of concrete security walls, barbed wire fences, LAPD swat teams, corruption, and racism, all of which appeared two years after he wrote the book, in the riots of 1992.

the riots seemed like the fulfillment of davis' prophesy, but still, some of davis' research has been criticized, and I must say that I found some of his claims a bit unbelievable, or at least questionable. For example, in the introduction, its impossible for him to overstate the size and importance of the l.a. region:

"Stretching now from the country-club homes of Santa Brbara to the shanty colonias of Ensenada, to the edge of Llano in the high desert and of the Coachella valley in the low, with a built-up surface area nearly the size of Ireland and a GNP bigger than India's - the urban galaxy dominated by Los Angelesis the fastest growing metropolis in the advanced industrial world."

The book is divided into seven chapters, beginning with a discussion of intellectuals' and artists' visions and versions of l.a., appropriate because "L.A. is probably the most mediated town in America, nearly unviewable, save through the fictive scrim of its mythologizers" (quoting Michael Sorkin). Dividing L.A.'s commentators into "boosters," "debunkers," and "noirs," Davis touches on how the booster-invented fantasy of the craftsman and Spanish colonial architectural style reflected the early 20th century "ideology of Los Angeles as the utopia of Aryan supremacism - the sunny refuge of White Protestant America in an age of labor upheaval and the mass immigration of Catholic and Jewish poor from Eastern and Southern Europe." Davis also details how noir authors' "petty-bourgeois anti-heroes typically expressed autobiographical sentiments, as the noir of the 1930's and 1940's (and again in the1960's) became a conduit for the resentment of writers in the velvet trap of the studio system," emphasizing the genre's "constant tension between the 'productive' middle class ([detectives like Phillip] Marlowe . . . ), and the 'unproductive' declasses or idle rich" who hire them.

Chapter two inspects the political and economic power structures that built and, perhaps, ruined los angeles. Constructed on land speculation, railroads, and eventually, shipping, agriculture and oil, l.a. really emerged as an urban center in the late 1800's and early 1900's, under the control of the downtown chandler and otis families, who owned - among other interests - the l.a. times. By the 1950's, the Hollywood / Jewish elites had solidified their power, and located on the Westside of town. By the 60's and 70's black and latino influence began to grow, culminating in the election of mayor Tom Bradley, and most recently, antonio villaraigosa. With political power now in the hands of historical minorities, and economic power shared with asian capital, l.a. is a city unique in that it is moving forward into an age characterized by shared and dispersed power.

The next chapters cover, respectively: suburban growth and the homeowner association-led backlash against it; wealthy residents' obsession with security; the battle between law enforcement and gangs; the catholic church; and the birth, death and rebirth of Fontana, an all-but insignificant city in most people's minds, but - not coincidentally - the childhood home of the author, which he dubs the "junkyard of dreams."

Although its hard to buy wholesale his hell-in-a-handbasket version of l.a., davis really makes the city's immense scale, impenetrable power structure, and ugly dark side live and breathe. And about halfway through, he managed to explain some of the bizarre and disjointed experiences I had on my trip:

"in other cities developers might have attempted to articulate the new skyscape and the old, exploiting the latter's extraordinary inventory of theatres and historic buildings to create a gentrified history - a gaslight district [in San Diego], Faneuil Market, or Ghirardelli Square - as a support to middle-class residential colonization. But Los Angeles's redevelopers viewed property values in the old Broadway core as irreversibly eroded by the area's very centrality to public transport, and especially its use by the Black and Mexican poor. . . . As a result, redevelopment massively reproduced spatial apartheid. The moat of the Harbor Freeway and the regarded palisades of Bunker Hill cut off the new financial core from the poor immigrant neighborhoods that surround it on every side."

Then comes the sledgehammer:

"The Downtown hyperstructure - like some Buckminster Fuller post-Holocaust fantasy - is programmed to ensure a seamless continuum of middle-class work, consumption and recreation, without unwonted exposure to Downtown's working class street environments. . . . [t]his is the archisemiotics of class war."

Perhaps, but perhaps not. And even if so, the more important question is: what of it? Or, what to do about it? Perhaps Davis answers some of these questions in the second and third installments of his L.A. trilogy, but my guess is I'll be enjoying more gloom and doom in book #2, "the ecology of fear." In other words, what Davis does, he does rather well. If you hate LA, you may enjoy "city of quartz." Although the author has claimed to have a deep and abiding love for the city, you wouldn't know it, other than from the breadth of his research. I do understand his point of view; LA is a pretty fucked-up place in a lot of ways, and those of us who have spent some time in the LA "urban galaxy" have probably had enough bizarre and disturbing experiences with the police, or years of simple, quiet, annonymous, lonely drives down a crowded freeway to sympathize. But as I get older, I have more of an appreciation for the sunshine, the feeling of being squarely between beach and mountains, and the post-traditionalist mentality. Davis has left out many of the things that make LA great: the sun setting over the ocean, the in-n-out burgers, the smiles (even if they are fake), the feeling of driving really, really fast down pacific coast highway or mullholland drive, the tall, gently swaying palm trees aginst a cloudless blue sky. To a native, reading "city of quartz" brings back a lot of memories, both bad and good, and at times, helps you realize why you see certain things the way you do. but to a non-native, you definitely want to take anything Mike Davis says with a grain of salt. i would recommend that grain include a trip to the area around pershing square.

Thursday, April 28, 2005

Ore-gone?

Portland, Orgeon

Photo by Hi-Cam Photography

government in the United States. Metro has earned a reputation for innovation in "smart growth," including mass transit and density initiatives, and the implementation of an urban growth boundary.

But Oregonians recently voted 60-40 in favor of Ballot measure 37, which would require local government agencies, including Metro, to compensate landowners when zoning changes affect their property values. And the law is retroactive, so if a property owner thinks any zoning change made during his tenure as owner has devalued his property, he can file a claim for compensation.

Measure 37 went into effect on December 3. No money was allocated to pay property owners' claims. If the legislature can't come up with the money by June 3, zoning changes will be waived and development will proceed largely free of the control of state land use planners. States with a similar law include Florida, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Texas.

The really interesting thing about Measure 37 getting passed is that before the vote, the referendum was being framed as a showdown between urban blue-staters and rural red-staters. An article in The Oregonian, the state's leading newspaper, portrayed the measure as pitting "people frustrated by run-ins with the government" against "people who tie Oregon's identity to its environment."

The real genius of the pro-37 campaign was convincing voters that a vote for 37 was a vote to safeguard rights, not curtail them. Proponents used the language of individual rights, rhetoric usually reserved to defend widely accepted civil liberties like free speech and the right to vote; not the right to sell property.

The effects remain to be seen, but I predict creeping sprawl like the kind in a lot of the rest of the country slowly taking hold in the Portland suburbs. Developers and some area residents will reap a short-term financial benefit. They will use the money to buy SUV's to drive and pick up fast food, and eat sitting at home playing video games, content in the knowledge that they have the freedom to do whatever they want, dammit, even if that means making a mess out of what once was the countryside.

Friday, March 04, 2005

Geographic Profile: Park Slope, Brooklyn

I moved to Park Slope in August 2004. When I told my grandma – a lifelong Brooklynite – where we bought a condo, she replied, “well that’s not a great area.” Of course, she was talking about 20 or 30 years ago. It turns out, the Slope today is a great area. The combination of beautiful 19th century architecture, a clear grid system of streets, and proximity to

7th avenue, looking north from about 8th street

Physical Design

Park Slope, as its name would suggest, is built on a gently sloping hill, with the park at the top. The neighborhood is defined by a grid system of streets, including two main commercial avenues – 5th and 7th – running north-south, and about 20 residential side streets running east-west, with the named and lower numbered streets at the northern end.

Both the streets and the avenues of the Slope have perfect proportions to accommodate a comfortable walking lifestyle. The avenues – lined with mostly four- and five-story buildings that are built fully out to the sidewalk – features only one lane of traffic in each direction, buffered from the curb by parked cars. The streets are mostly one-way, except for

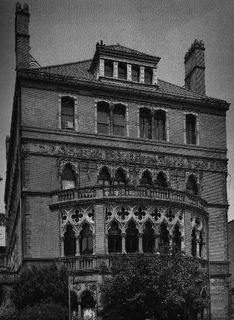

the litchfield villa, built in the 1850's in what is now the western edge of prospect park. mr. litchfield owned much of what is now park slope.

History

a typical park slope street

Culture

Park Slope has a reputation as a politically progressive activist community. Much effort has been expended in the preservation of the historic integrity of the neighborhood, and Park Slope is the “Recycling Capital” of

Social concerns also occupy a high place on the neighborhood’s agenda. The area is home to numerous civic, merchant and social organizations that offer many forums for social discourse. The Park Slope Food Co-op is the largest member-owned and operated food co-op in the country, with over 10,000 members, many of whom participate on the Co-op’s political committees, addressing issues like genetically modified foods and the use of pesticides. The area also prides itself on its diversity and contains a spectrum of socioeconomic, ethnic, and cultural backgrounds. For example, it has the highest lesbian population in the City and has played host to

Of course, when walking the streets of Park Slope, you can’t help but notice all the babies, and all the yuppies. It seems like as soon as

the montauk club on 8th avenue

"Gentrification?"

As you can tell, there are many things I love about my neighborhood, but I tend to have mixed feelings about gentrification. On one level, it is clear that the neighborhood's hot real estate market is driving out families who will have to find another place to live. But that has already happened in Manhattan; which is why more people are moving into the Slope to begin with. I always feel awkward walking home from work in my business suit past the stoop-sitters who camp out all day on my block. But my family also has history in Park Slope. At the turn of the century, my Russian immigrant great grandfather owned a grocery store on 5th avenue, and he lived with his family on 6th avenue at 11th street until roughly the mid-1920's. So it seems different families have been replacing eachother for generations. Gentrification is often discussed in terms of it being a problem, but it is a complex topic, especially in relentlessly free-market American cities like New York, where everybody wants a piece of the same pie.

Monday, January 31, 2005

book review: dolores hayden, "building suburbia" & "field guide to sprawl"

In her two most recent publications, Dolores Hayden looks long and hard at suburban development patterns, and comes up with not only a way of contextualizing the decentralized built environment many of us find ourselves in, but also proposes some ideas as to how to improve it.

In "Building Suburbia," Hayden analyzes the patterns of government-subsidized private development outside of America's major city centers. She proceeds in chronological order, beginning in 1820, and continues thorough the present and near future, assessing prevalent development trends, and assigning catchy - if derisive - nicknames to nine types of suburban development characteristic of specific historical eras: "borderlands" (beginning circa 1820’s) "picturesque enclaves" (1850’s) "streetcar buildouts" (1870’s) "mail order and self built suburbs" (1900’s) "sitcom suburbs" (1940’s) "edge nodes" (1960’s) and "rural fringes" (1980’s-present).

Hayden shows through careful research how each type of pattern emerged, and by the book’s end, it becomes clear that the majority of suburban development was the product of years of builders' and regulators' intensive efforts at maximizing private profit at public expense. It may seem obvious when so stated that home building, like any other american industry, seeks a maximum return on profit and a comfortable regulatory environment in which to operate. But parts of this book are fascinating in the details of just how that regulatory environment was created, and the how decades of profit maximization in the suburban home and commercial building industries has shaped the daily experience of most americans. With a clear post-modern perspective, Hayden notes the racial, class, gender and environmental problems caused or exaccerbated by suburban development. And ever so rarely, she points out admirable attempts at good suburban design. The book begins with an examination of the group dynamic present in the early nineteenth-century suburban push. Hayden examines the tendencies toward upper-class communal country living, and includes many diagrams and pictures. She continues with the advent of streetcar suburbs, and the bizarre phenomenon of mail-order suburbs. The truly fascinating sections begin in the chapter on "sitcom suburbs,” when it becomes clear that the suburbs are no longer places to escape urban capitalism. Hayden begins one paragraph: "developers liked to say that the aquisition of a single family house and the process of furnishing and expanding it made blue collar residents ‘middle-class.’" It was also said that people who owned a suburban home and car(s) had to keep so busy to pay for their posessions that they could be counted on not to turn “communist.” In this respect, Hayden points out how suburban development became the heart of american capitalism and lent credence to the ideal of an open-class society.

By the 1950's, "vast american suburbs of the post-WWII era were shaped by legislative processes reflecting the power of the real estate, banking, and construction sectors, and the relative weakness of the planning and design professions." Among other key 20th century legislative changes, Hayden notes the rewriting of the federal tax code to permit write-offs for home mortgage payments and accellerated depreciation of the taxable value of new commercial construction in "greenfield" (i.e., open) areas. These innovations encouraged larger, more expensive homes, and cheaply made, poorly maintained shopping malls. In addition, the automobile, gas and cement lobbies combined to undermine earlier attempts at more dense, transport-efficient "streetcar suburbs," like Brooklyn Heights, New York. Eventually, most suburban residents became dependent on automobiles for basic needs, and automobiles, in turn, blew up the scale of suburban development, such that every home needed a garage or two, and every civic location needed expansive asphalt fields of parking.

Thus, by the end of the 20th century, upwardly mobile people came to live in huge homes located in far-flung and virtually random agglomerations of other huge homes, big-box retail stores, fast-food restaurants, freeways and office parks. Hayden examines the problems created by this set-up: long distances and high costs of car and home ownership combining to oppress low-wage service workers and immigrant nannies; asphalt runoff, auto exhaust and overextended infrastructure polluting the air and water; and a pervasive sense of placelessness and isolation. However, she almost completely ignores the segment of the population that is perfectly happy living in the suburbs. In that respect, her thesis is not comprehensive. She either assumes what she set out to prove – that the greater good served by reforming current development trends is paramount – or she assumes that the people who enjoy the ‘burbs – if they exist – are such a small contingent that they are not worth discussing.After describing the ills of sprawl, Hayden goes in search of solutions. She intelligently discusses the plusses and minusses of green building, "new urbanism," Disney-esque theme park developments, and the ever-so-creepy "house_n," designed by M.I.T. students and funded by – among other corporations – Proctor & Gamble and International Paper. However, Hayden believes these types of design innovations will not solve the problem entirely. She advocates for regional solutions, including the rebuilding of older suburbs, keeping in mind which of the historic development patterns originally created a particular place.

Of course, to completely re-value older suburbs, the federal tax code would have to be revised. But in the mean time, Hayden points to instances of thoughtful suburban design in projects like H.U.D.'s Concord Village in Inianapolis, which took account of historical building patterns of older suburbs in the area, and built houses consistent in scale and design.Hayden summarizes suburbia as "the hinge, the connection between past and future, between old inequalities and new possibilities. In all kinds of existing suburbs, inequalities of gender, class and race have been embedded in material form. So have unwise environmental choices." She concludes, "to preserve, renovate, and infill the suburban neighborhoods of the past can make the suburban city more egalitarian and sustainable."

These are admirable goals, and Hayden makes a good case for how and why to work toward them. And, thankfully, she includes many interesting diagrams and pictures. The question remains: is this what actual suburban residents actually want? And do their views matter? A recent New York Times article suggests that dense, walkable suburban development only commands 10% of new housing market demand.

In the “Field Guide to Sprawl” Hayden goes a step further with her descriptions of suburban development patterns. She combines crisp aerial photography of specific features of suburban “sprawl” with brief explanations of the snappy names given to such features by smug journalists and distressed planners and architects. Even more so than in Building Suburbia, it is clear that Hayden harbors not only a fascination, but also a distaste with conventional suburban development. In addition to the better known terms like "strip mall," Hayden provides some other keenly descriptive terms, like "edge node," "alligator," "zoomburb,” "parsley around the pig" and "pig in the python."

As is clear from those examples, this is, at its core, a book of jargon. And, as is the nature of jargon, the terms themselves are meaningless without decent explanation. Hayden provides good explanations sometimes, and some terms like edge node are almost self-explanatory. But other times, one wonders whether it will in fact be possible to identify the more obscure suburban features in real life, especially from the window of a passing car. And even assuming one can identify one feature or another, will anybody in the car understand when you say “hey, look, an alligator”? Nevertheless, it's a quick read, and especially if one harbors Hayden’s same slightly repulsed curiosity with suburbia, one will find it a thoroughly enjoyable – if not entirely useful – reading experience.

For more on what actual suburbanites actually want, see Robert Johnson, "Why 'New Urbanism' Isn't for Everyone," N.Y. Times (Feb. 20, 2005).